We had really high hopes for Tajikistan as we really love mountains, and this is where the Pamirs are located. Our desire to reach the mountains was further enhanced by our wish to get away as soon as possible from the sickening heat of the plains that we’d had to endure for weeks in a row - basically ever since we had arrived in Georgia. We had really grown tired of our clothes being drenched with sweat all the time. So once we had crossed the border with our e-visas (a great move from Tajikistan to switch to this handy option - you apply and pay the 70 USD online, and receive the printout visa the next day), we zoomed towards the province of Gorno-Badahshan. This is where the bigger part of the Pamir mountains lies and since it is semi-autonomous, a special permit is required to visit the area (now that the e-visa has been introduced, it is possible to get the “permit” which is really nothing more than a stamp on the visa together with the visa itself).

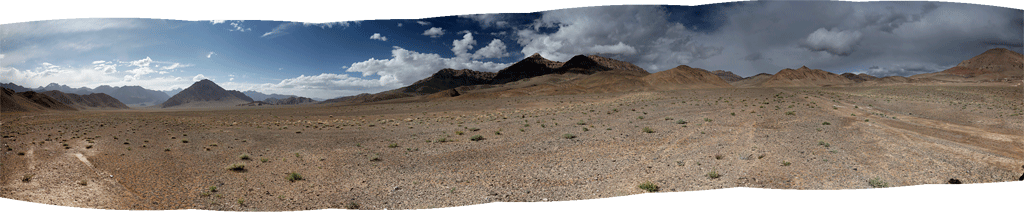

Even though Tajikistan is not really a huge country (with its 143 000 sq km it is only three times the size of our tiny Estonia), it still took some time to get to the mountains proper. The western part of the country sports nothing taller than hills, so our first night turned out to be a sweaty hell. The hill that we’d decided to set up camp on had obviously absorbed so much heat during the day that it kept radiating it throughout the night and even by morning, when the outside air was really cool, the ground underneath our mattresses was still very warm to the touch.

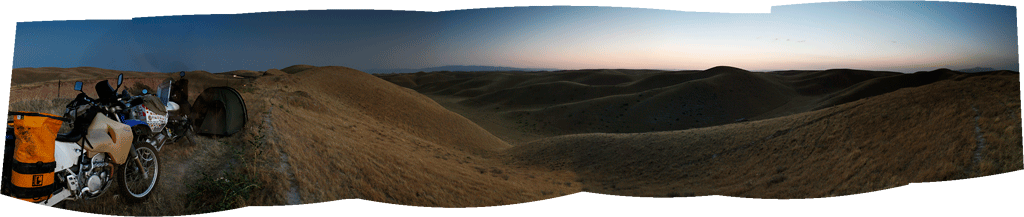

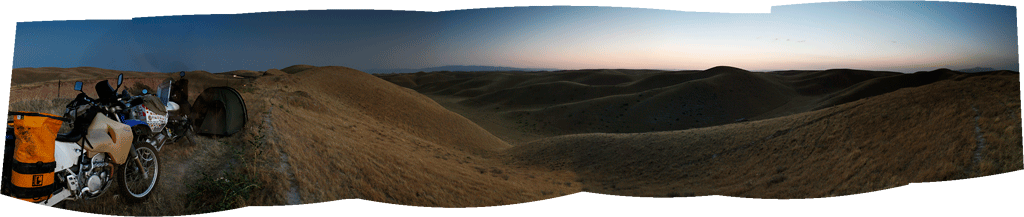

Hissar sunset.

Wild camp in the Hissar mountains.

As we got out of the heat of the tent and into the refreshing coolness of the pre-sunrise morning, we ate some bread and super tasty grapes we’d bought from a roadside vendor before heading south. Soon we arrived by Panj river that makes up the natural border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. At first, the river was pretty wide, but was we rolled along it and upstream, it became more and more narrow, bringing us closer and closer to Afghanistan on the other side. At some points, we were only some 50 meters or basically a stone’s throw away from Afghanistan.

I know it kind of sounds dangerous, but in reality the area of Afghanistan that we were skirting - the so-called Wakhan Corridor, is probably the safest. Nestled between Pakistan and Tajikistan as a result of the Great Game, the narrow strip hosts some pretty high mountains and a few sleepy villages that are connected by nothing than a rough track running along the river. If it weren’t so expensive to get there with your own vehicle, we would probably have gone across and ridden the length of the border on the other side of the river. However, riding on the Tajikistan side surely gave us better views of Afghanistan (and sometimes even some peaks in Pakistan, as the “corridor” is really only so wide).

We ended up riding along Panj river for a few hundred kilometres, and since the road was in a pretty bad shape, we didn’t manage to go too fast. For a few nights we found ourselves camping spots with a good view of what was happening in Afghanistan, thus calling them the “Afghan cinema” between the two of us. For the first night, we settled in a place where the cliffs on the both sides were so tall and the riverbed was so narrow, that we felt like we were spending a night in a cathedral. As the sun set and it got dark, we witnessed a lot of movement on the Afghanistan side - we could see small bikes (with traditional music blaring as they passed) bouncing down the track cut into the sheer rock a mere 100 meters from us. The track seemed pretty busy, so we wandered if there was some smuggling going on (according to various sources, there surely is), or of they were regular village folk.

The huge rocky wall behind us is already Afghanistan.

The further we rode the next day, the better were the views (but no real improvement in air temperature as we were gaining altitude very slowly).

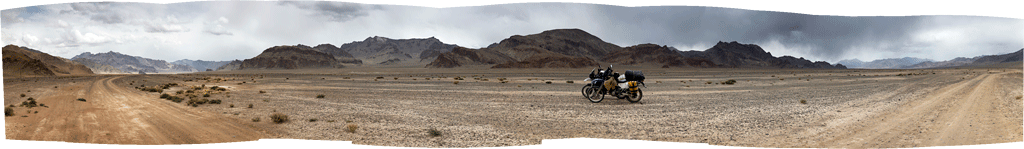

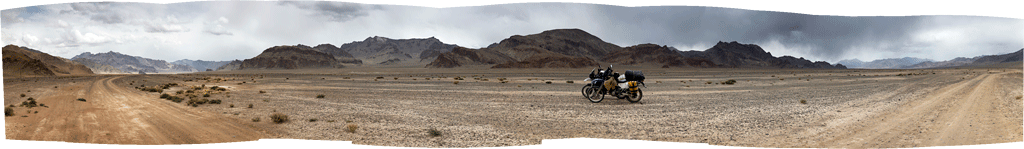

Riding through Pamirs...

Abandoned truck on Pamir Highway.

Gorno-Badakhshan. We started gaining more altitude...

Why you should never-ever ride at night in the Third World.

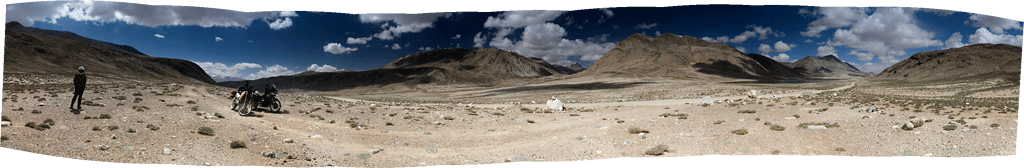

The magnificent Pamir mountains.

Panorama with Afghanistan village from other side of the Panj river.

The ancient Fort Yamchun, at over 3000 meters up it was very hard to conquer.

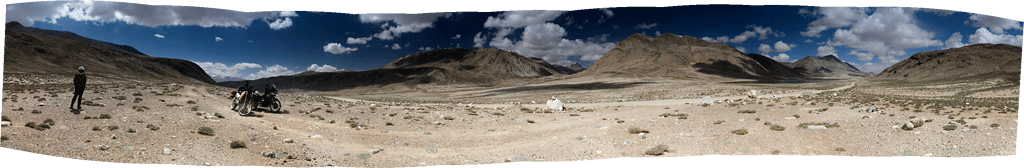

Views from the Pamir Highway...

Wakhi girl.

Ancient Buddhist remains in Vrang.

DRZ got tired?

A peak peeking over the Wakhan corridor.

As we passed the village of Langar, the road swiftly started climbing uphill, one bend after another. We said farewell to River Panj that we’d been riding a long for a couple of days, as well as to Afghanistan, as the road (that now had become nothing more than a track) turned north. The further up we moved, the colder it got, and the clouds that hung just above the mountain tops promised some rain.

Track on the left is Afghanistan.

With the landscape turning more and more vertical, we became unsure as to if we would be able to find a decent spot to pitch our tent. In most places the ground was covered with rock debris, and was totally exposed to the wind that kept gathering power. But as we were about to lose hope, a nearly perfect spot opened up in front of us as we came out of one bend. We actually managed to erect our tent on nice green grass in some ditch that probably overflows with water when it rains up in the mountains - so we really hoped that it would not rain.

We were lucky - it did not rain, and there wasn’t even much wind, even though it was pretty cold at night. The next day we crossed the Khargush Pass at some 4344 meters. In fact, it did not really feel like crossing a pass at all, as most of the passes that we’d crossed before (in Chile or India, for example) had been really steep and we’d had to do a lot of switchbacks to get up and down those passes. This one was different as the ascent near the pass was really gentle.

Off the beaten track.

Herder boys at over 4000 meters above sea level. They asked for a smoke.

After Khargush pass.

Panorama of Chukurkul (lake situated at 2970 meters above sealevel)

Soon after Khargush we arrived on the “main road” or the Pamir Highway proper. The highway runs from Khorog, the capital of Horno-Badakshon province, to the village of Murgab and on towards Kyrgyzstan. But although we’d planned on enjoying some tarmac whilst riding directly to Murgab, we thought - why not make a small detour and go to “the coldest place in Tajikistan”, or the village of Bulunkul just 16 km away from the main road.

Bulunkul village with a dust devil.

As we arrived we looked up some homestay (in Tajikistan, many homes are set up to receive guests - most often very basic, with dorm-style accommodation and long drop toilets) and asked if we could have something to eat there. Soon we were served some delicious fried fish from the nearby lake, together with hot green tea. It felt so nice to sit inside, while we could hear the wind whistling outside.

Eating fish from Bulunkul lake.

As we’d finished, we stepped outside to be hit by a major sandstorm. For a few minutes we could not see anything. But it ended just as abruptly as it had begun, allowing us to take a few shots of the village. At the altitude of around 3600 meters, the white washed buildings had a special glow, adding to the somewhat end-of-the-road atmosphere of the village.

Bulunkul village.

They build their houses from all sorts of stuff, at the coldest spot in the country you need a good heating though...

Our GPS map indicated that there are more options of getting back onto the main road than just backtracking, so we decided to try some offload tracks.

It was a good decision, as the landscapes became more and more majestic. At one point we came across a spot that we thought was excellent for camping. But as we were about to set up camp, I started feeling unwell. Being at the altitude of some 3900 meters, it was likely that my body hadn’t quite adapted to the altitude and hence the oncoming weakness, headache and nausea. Having gone through some serious altitude years ago in Bolivia, we didn’t want to risk it and decided to pack up and try to get back to civilisation in case I would get worse. And as we headed down the track towards the village of Alichur on the main road, I was getting worse. The track was degrading more and more, until the barely recognisable wheel tracks disappeared completely in some swamp. But the GPS kept us assured that we were on the right “track”, so we dragged our bikes through the slush and managed to track down the wheel tracks on the other side of it.

I must admit that as the sun was about to set, the light play was amazing - but we would not dare to stop for pictures. Instead, we pushed on, at an ever growing pace, to make it to the village. Eventually we did. The sun set just minutes after we’d arrived at some roadside canteen and asked if we could spend the night there. For USD 2,50 per person, we were allowed to stay the night. It turned out to be a terrible one, as I kept vomiting and even at those moments where I briefly fell asleep, I was every time awaken by the lights of the trucks running down the Pamir Highway that were coming from China.

The morning was just as bad, so even though we thought it would be unlikely, we inquired about a doctor in the village. Soon, a guy rolled up on his old UAZ and told me to get in. We went to the other side of the village down a muddy track where there was a small medical post indeed. After some waiting and a short gesture-language conversation I was sent back with a small ziplock bag full of pills that I didn’t even know the name of.

Alichur doctor's appointment door.

Not sure if it was the anonymous medicine, or I was slowly adapting to the altitude, but a few hours later I was feeling slightly better so I even managed to eat some soup and drink some tea without vomiting.

After ate those, I had to vormit all out. Altitude sickness really sucks...

By late afternoon we were quite tired of staying inside one room, so we decided to go for a short stroll in the village. Talking to the villagers, we found out that in that nondescript, windswept village there is even a school with 250 pupils (some of them from nearby villages).

Alichur's English teacher, she has around 250 students to take care of. She's a native Tajik, they look like souther-europeans.

As we left Alichur after having spent there two nights, we rolled on to Murghab. I knew that there was supposed to be an astronomical observatory nearby, and even though allegedly no foreigners were allowed to visit it, I really wanted to go and at least get a glimpse of it. Actually, it isn’t special in any way (at least not that we know of), but as I have huge interest in astrophysics, I had the feeling that we should go and look it up.

The slight problem was that we didn’t have a good clue as to where exactly it was supposed to be (only a rough indication on a large-scale map), so all we could do is head out into the mountains in that rough direction and hope that it would pop out somewhere on the horizon at some point. First, of course, we filled our tanks in Murghab:

Stocking up some of the rust-particle infested low-quality fuel. Our trusty old beemer drinks it well.

Then we headed east towards the Chinese border. First, the road was pretty good, but then it started degrading rapidly, turning into a mere track. The vistas, however, got better and better by the kilometre.

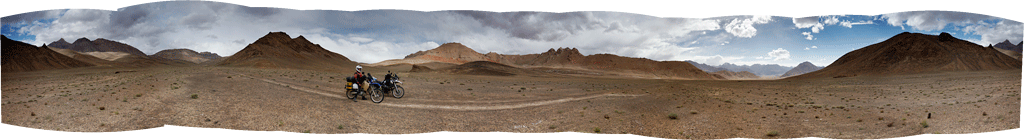

At one point we left that track and headed deeper into the mountains, where even more surreal landscapes opened up before us. Our GPS map indicated that some crater was supposed to be located there, but we could not make out any crater-like formations. Then we figured that it must have been so huge that we were actually inside the crater.

Numerous tracks ran across its bottom in various directions, and we had no idea which one of them, if any, could take us to the observatory. So we picked one and followed it, while scanning the mountains with our eyes to try to notice something that might resemble an observatory.

After some kilometres of riding, the track was barely there, but the good news was that we noticed a dot on top of one of the mountains that looked like a man-made structure. We looked up our binoculars and… it really was an observatory! There was quite a distance between us and the observatory though, and there didn’t appear to be any track going up the rather steep mountain side, so we hoped that following the vague track would eventually lead us to an access point.

We followed the ever-fading track, until it was nothing more than a vague imprint of car wheels on the rocky surface. We almost lost it as we found ourselves riding in a dry riverbed and across some serious rocks - the indication that someone had been there before us (even if it was just one car months ago) kept us pushing. After a few hundred meters of the riverbed we saw the tyre tracks heading up a steep hill, and we followed them religiously. We’d long lost the view of the metallic dome of the observatory, but we still hoped we would get there.

Pushing the bikes to their limits, at one point we realised that we’d come to the altitude of some 4300 meters. We admitted to ourselves that we could not stay at that altitude for long. Having just barely adapted to 3800 meters, the risk of being struck by altitude sickness was too real - or rather a matter of hours. Miles and miles away from civilisation, with the only indication of any human activity being that vague set of tyre tracks, it could have been a matter of life and death.

In the last effort to get another glimpse of the observatory, I rode up another steep hillside, ascending some 200 meters more, which did bring the dome back in sight, but it was still very far away.

Took a natural mountain at 4300 meters - no track what so ever, just a steep rocky climb.

See the two dots - those are the two small telescope domes of Tajikistan observatory. That's the closest I could get.

We turned around and descended in a rush. As we got back to safer altitudes, we had two options - whether to go back to Murghab the way we had come, or try to continue. Unwilling to back track, we opted for the second option, even though our GPS showed the track to break up in quite a few places.

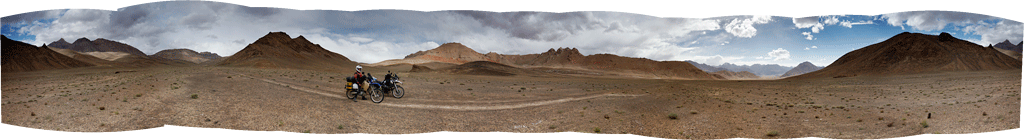

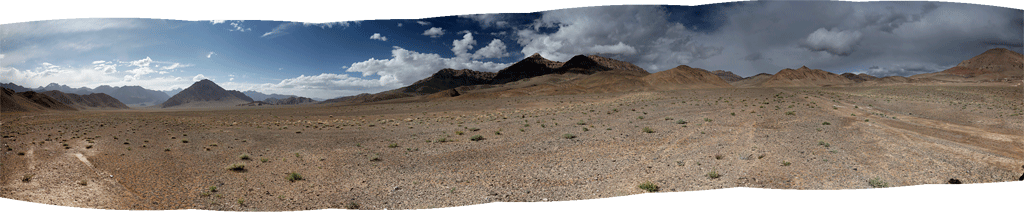

(Click to enlarge panoramas, and click again on the big one to horizontally scroll to get the actual feeling of the place, see the track we rode too)

Just as expected, the track became more and more difficult, as we had to navigate through quite a few of (both dry and wet) river beds. At points, we lost the track altogether, and we even got some snow.

DRZ got tired?

Last second high speed stop never ends well over a ditch...

Finally, we did manage to get back onto the main road, although honestly, quite many times before that we had caught ourselves thinking that should the track become even more technical, we might have turn around and go back all the way we’d come.

Remains of Marco Polo sheep.

Tajik girl.

From Murghab, we headed north. The road kept ascending slowly, but surely, and as the border roads normally do, it kept degrading bit by bit. Knowing that we had the crossing of the tallest passes - Ak-Baital, also marking the border between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan - ahead on that same day, we didn’t want to spend unnecessary time on taking photos. Rather we wanted to get across as soon as possible not to get stranded at high altitude and risk altitude sickness symptoms again. Anyway, the weather wasn’t the most photogenic, at least not until we reached Karakol, the last village before the border. The lake with the same name, stretching 52 kilometres and lying at the altitude of 3900 meters, looked quite stunning. Contrary to its name (karakol means “black lake”), its waves were mesmerisingly blue.

Karakol lake panorama.

The village itself, located a few dozen kilometres from the border post, looked unexpectedly shabby, not to say half-abandoned, not doing any justice to the magnificent lake side setting. After we’d filled our bellies with some sad vegetable soup at the only eatery of the village, we rushed towards the border. The road was getting worse, featuring some of the worst washboard we’d ever experienced.

Some distance before the border post, the broad, straight road turned rather curvy and steep, taking us to the Tajik border post. The formalities were unusually quick (perhaps the border guards have been advised not to keep people at the altitude for too long), and before we knew, we were on the road again, heading towards the Ak-Baital or the White Horse pass at the altitude of 4655 meters.

They say gravity is lower at higher altitudes (4655 meters above sealevel).

And for those who're interested, I'll put a shameless ad about the book we're self-publishing through kickstarter. Or more info here.

Or more info here.

The crowdfunding project is up for just a few more days, but quite a few "kicks" are still missing.

Cheers,

Margus & Kariina

Even though Tajikistan is not really a huge country (with its 143 000 sq km it is only three times the size of our tiny Estonia), it still took some time to get to the mountains proper. The western part of the country sports nothing taller than hills, so our first night turned out to be a sweaty hell. The hill that we’d decided to set up camp on had obviously absorbed so much heat during the day that it kept radiating it throughout the night and even by morning, when the outside air was really cool, the ground underneath our mattresses was still very warm to the touch.

Hissar sunset.

Wild camp in the Hissar mountains.

As we got out of the heat of the tent and into the refreshing coolness of the pre-sunrise morning, we ate some bread and super tasty grapes we’d bought from a roadside vendor before heading south. Soon we arrived by Panj river that makes up the natural border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. At first, the river was pretty wide, but was we rolled along it and upstream, it became more and more narrow, bringing us closer and closer to Afghanistan on the other side. At some points, we were only some 50 meters or basically a stone’s throw away from Afghanistan.

I know it kind of sounds dangerous, but in reality the area of Afghanistan that we were skirting - the so-called Wakhan Corridor, is probably the safest. Nestled between Pakistan and Tajikistan as a result of the Great Game, the narrow strip hosts some pretty high mountains and a few sleepy villages that are connected by nothing than a rough track running along the river. If it weren’t so expensive to get there with your own vehicle, we would probably have gone across and ridden the length of the border on the other side of the river. However, riding on the Tajikistan side surely gave us better views of Afghanistan (and sometimes even some peaks in Pakistan, as the “corridor” is really only so wide).

We ended up riding along Panj river for a few hundred kilometres, and since the road was in a pretty bad shape, we didn’t manage to go too fast. For a few nights we found ourselves camping spots with a good view of what was happening in Afghanistan, thus calling them the “Afghan cinema” between the two of us. For the first night, we settled in a place where the cliffs on the both sides were so tall and the riverbed was so narrow, that we felt like we were spending a night in a cathedral. As the sun set and it got dark, we witnessed a lot of movement on the Afghanistan side - we could see small bikes (with traditional music blaring as they passed) bouncing down the track cut into the sheer rock a mere 100 meters from us. The track seemed pretty busy, so we wandered if there was some smuggling going on (according to various sources, there surely is), or of they were regular village folk.

The huge rocky wall behind us is already Afghanistan.

The further we rode the next day, the better were the views (but no real improvement in air temperature as we were gaining altitude very slowly).

Riding through Pamirs...

Abandoned truck on Pamir Highway.

Gorno-Badakhshan. We started gaining more altitude...

Why you should never-ever ride at night in the Third World.

The magnificent Pamir mountains.

Panorama with Afghanistan village from other side of the Panj river.

The ancient Fort Yamchun, at over 3000 meters up it was very hard to conquer.

Views from the Pamir Highway...

Wakhi girl.

Ancient Buddhist remains in Vrang.

DRZ got tired?

A peak peeking over the Wakhan corridor.

As we passed the village of Langar, the road swiftly started climbing uphill, one bend after another. We said farewell to River Panj that we’d been riding a long for a couple of days, as well as to Afghanistan, as the road (that now had become nothing more than a track) turned north. The further up we moved, the colder it got, and the clouds that hung just above the mountain tops promised some rain.

Track on the left is Afghanistan.

With the landscape turning more and more vertical, we became unsure as to if we would be able to find a decent spot to pitch our tent. In most places the ground was covered with rock debris, and was totally exposed to the wind that kept gathering power. But as we were about to lose hope, a nearly perfect spot opened up in front of us as we came out of one bend. We actually managed to erect our tent on nice green grass in some ditch that probably overflows with water when it rains up in the mountains - so we really hoped that it would not rain.

We were lucky - it did not rain, and there wasn’t even much wind, even though it was pretty cold at night. The next day we crossed the Khargush Pass at some 4344 meters. In fact, it did not really feel like crossing a pass at all, as most of the passes that we’d crossed before (in Chile or India, for example) had been really steep and we’d had to do a lot of switchbacks to get up and down those passes. This one was different as the ascent near the pass was really gentle.

Off the beaten track.

Herder boys at over 4000 meters above sea level. They asked for a smoke.

After Khargush pass.

Panorama of Chukurkul (lake situated at 2970 meters above sealevel)

Soon after Khargush we arrived on the “main road” or the Pamir Highway proper. The highway runs from Khorog, the capital of Horno-Badakshon province, to the village of Murgab and on towards Kyrgyzstan. But although we’d planned on enjoying some tarmac whilst riding directly to Murgab, we thought - why not make a small detour and go to “the coldest place in Tajikistan”, or the village of Bulunkul just 16 km away from the main road.

Bulunkul village with a dust devil.

As we arrived we looked up some homestay (in Tajikistan, many homes are set up to receive guests - most often very basic, with dorm-style accommodation and long drop toilets) and asked if we could have something to eat there. Soon we were served some delicious fried fish from the nearby lake, together with hot green tea. It felt so nice to sit inside, while we could hear the wind whistling outside.

Eating fish from Bulunkul lake.

As we’d finished, we stepped outside to be hit by a major sandstorm. For a few minutes we could not see anything. But it ended just as abruptly as it had begun, allowing us to take a few shots of the village. At the altitude of around 3600 meters, the white washed buildings had a special glow, adding to the somewhat end-of-the-road atmosphere of the village.

Bulunkul village.

They build their houses from all sorts of stuff, at the coldest spot in the country you need a good heating though...

Our GPS map indicated that there are more options of getting back onto the main road than just backtracking, so we decided to try some offload tracks.

It was a good decision, as the landscapes became more and more majestic. At one point we came across a spot that we thought was excellent for camping. But as we were about to set up camp, I started feeling unwell. Being at the altitude of some 3900 meters, it was likely that my body hadn’t quite adapted to the altitude and hence the oncoming weakness, headache and nausea. Having gone through some serious altitude years ago in Bolivia, we didn’t want to risk it and decided to pack up and try to get back to civilisation in case I would get worse. And as we headed down the track towards the village of Alichur on the main road, I was getting worse. The track was degrading more and more, until the barely recognisable wheel tracks disappeared completely in some swamp. But the GPS kept us assured that we were on the right “track”, so we dragged our bikes through the slush and managed to track down the wheel tracks on the other side of it.

I must admit that as the sun was about to set, the light play was amazing - but we would not dare to stop for pictures. Instead, we pushed on, at an ever growing pace, to make it to the village. Eventually we did. The sun set just minutes after we’d arrived at some roadside canteen and asked if we could spend the night there. For USD 2,50 per person, we were allowed to stay the night. It turned out to be a terrible one, as I kept vomiting and even at those moments where I briefly fell asleep, I was every time awaken by the lights of the trucks running down the Pamir Highway that were coming from China.

The morning was just as bad, so even though we thought it would be unlikely, we inquired about a doctor in the village. Soon, a guy rolled up on his old UAZ and told me to get in. We went to the other side of the village down a muddy track where there was a small medical post indeed. After some waiting and a short gesture-language conversation I was sent back with a small ziplock bag full of pills that I didn’t even know the name of.

Alichur doctor's appointment door.

Not sure if it was the anonymous medicine, or I was slowly adapting to the altitude, but a few hours later I was feeling slightly better so I even managed to eat some soup and drink some tea without vomiting.

After ate those, I had to vormit all out. Altitude sickness really sucks...

By late afternoon we were quite tired of staying inside one room, so we decided to go for a short stroll in the village. Talking to the villagers, we found out that in that nondescript, windswept village there is even a school with 250 pupils (some of them from nearby villages).

Alichur's English teacher, she has around 250 students to take care of. She's a native Tajik, they look like souther-europeans.

As we left Alichur after having spent there two nights, we rolled on to Murghab. I knew that there was supposed to be an astronomical observatory nearby, and even though allegedly no foreigners were allowed to visit it, I really wanted to go and at least get a glimpse of it. Actually, it isn’t special in any way (at least not that we know of), but as I have huge interest in astrophysics, I had the feeling that we should go and look it up.

The slight problem was that we didn’t have a good clue as to where exactly it was supposed to be (only a rough indication on a large-scale map), so all we could do is head out into the mountains in that rough direction and hope that it would pop out somewhere on the horizon at some point. First, of course, we filled our tanks in Murghab:

Stocking up some of the rust-particle infested low-quality fuel. Our trusty old beemer drinks it well.

Then we headed east towards the Chinese border. First, the road was pretty good, but then it started degrading rapidly, turning into a mere track. The vistas, however, got better and better by the kilometre.

At one point we left that track and headed deeper into the mountains, where even more surreal landscapes opened up before us. Our GPS map indicated that some crater was supposed to be located there, but we could not make out any crater-like formations. Then we figured that it must have been so huge that we were actually inside the crater.

Numerous tracks ran across its bottom in various directions, and we had no idea which one of them, if any, could take us to the observatory. So we picked one and followed it, while scanning the mountains with our eyes to try to notice something that might resemble an observatory.

After some kilometres of riding, the track was barely there, but the good news was that we noticed a dot on top of one of the mountains that looked like a man-made structure. We looked up our binoculars and… it really was an observatory! There was quite a distance between us and the observatory though, and there didn’t appear to be any track going up the rather steep mountain side, so we hoped that following the vague track would eventually lead us to an access point.

We followed the ever-fading track, until it was nothing more than a vague imprint of car wheels on the rocky surface. We almost lost it as we found ourselves riding in a dry riverbed and across some serious rocks - the indication that someone had been there before us (even if it was just one car months ago) kept us pushing. After a few hundred meters of the riverbed we saw the tyre tracks heading up a steep hill, and we followed them religiously. We’d long lost the view of the metallic dome of the observatory, but we still hoped we would get there.

Pushing the bikes to their limits, at one point we realised that we’d come to the altitude of some 4300 meters. We admitted to ourselves that we could not stay at that altitude for long. Having just barely adapted to 3800 meters, the risk of being struck by altitude sickness was too real - or rather a matter of hours. Miles and miles away from civilisation, with the only indication of any human activity being that vague set of tyre tracks, it could have been a matter of life and death.

In the last effort to get another glimpse of the observatory, I rode up another steep hillside, ascending some 200 meters more, which did bring the dome back in sight, but it was still very far away.

Took a natural mountain at 4300 meters - no track what so ever, just a steep rocky climb.

See the two dots - those are the two small telescope domes of Tajikistan observatory. That's the closest I could get.

We turned around and descended in a rush. As we got back to safer altitudes, we had two options - whether to go back to Murghab the way we had come, or try to continue. Unwilling to back track, we opted for the second option, even though our GPS showed the track to break up in quite a few places.

(Click to enlarge panoramas, and click again on the big one to horizontally scroll to get the actual feeling of the place, see the track we rode too)

Just as expected, the track became more and more difficult, as we had to navigate through quite a few of (both dry and wet) river beds. At points, we lost the track altogether, and we even got some snow.

DRZ got tired?

Last second high speed stop never ends well over a ditch...

Finally, we did manage to get back onto the main road, although honestly, quite many times before that we had caught ourselves thinking that should the track become even more technical, we might have turn around and go back all the way we’d come.

Remains of Marco Polo sheep.

Tajik girl.

From Murghab, we headed north. The road kept ascending slowly, but surely, and as the border roads normally do, it kept degrading bit by bit. Knowing that we had the crossing of the tallest passes - Ak-Baital, also marking the border between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan - ahead on that same day, we didn’t want to spend unnecessary time on taking photos. Rather we wanted to get across as soon as possible not to get stranded at high altitude and risk altitude sickness symptoms again. Anyway, the weather wasn’t the most photogenic, at least not until we reached Karakol, the last village before the border. The lake with the same name, stretching 52 kilometres and lying at the altitude of 3900 meters, looked quite stunning. Contrary to its name (karakol means “black lake”), its waves were mesmerisingly blue.

Karakol lake panorama.

The village itself, located a few dozen kilometres from the border post, looked unexpectedly shabby, not to say half-abandoned, not doing any justice to the magnificent lake side setting. After we’d filled our bellies with some sad vegetable soup at the only eatery of the village, we rushed towards the border. The road was getting worse, featuring some of the worst washboard we’d ever experienced.

Some distance before the border post, the broad, straight road turned rather curvy and steep, taking us to the Tajik border post. The formalities were unusually quick (perhaps the border guards have been advised not to keep people at the altitude for too long), and before we knew, we were on the road again, heading towards the Ak-Baital or the White Horse pass at the altitude of 4655 meters.

They say gravity is lower at higher altitudes (4655 meters above sealevel).

And for those who're interested, I'll put a shameless ad about the book we're self-publishing through kickstarter.

Or more info here.

Or more info here.The crowdfunding project is up for just a few more days, but quite a few "kicks" are still missing.

Cheers,

Margus & Kariina